The suicidality of adolescents and young adults in Luxembourg did not change significantly during the pandemic. However, this is no cause for relief: the current data from the Youth Survey Luxembourg indicate an increase in feelings of sadness and hopelessness, which can often be a precursor of suicidal ideation. In addition, researchers explain that higher suicide rates often only become apparent with a delay after a crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic sparked a public debate about mental health and well-being. Fears about a rise in suicides among young people grew stronger, because they are particularly susceptible to psychological problems, especially in adolescence. Since the contact restriction measures of the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected young people’s lives, further concerns were raised that this may amplify youth suicidality in Luxembourg (see also: Happy in COVID-19 times?).

This policy brief aims to provide empirical evidence to the debate. Based on the report “Suizidgedanken und -verhalten Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Luxemburg. Zeigen sich Effekte der Covid-19-Pandemie?” (Schomaker & Samuel 2022), we describe the changes in reported suicidal thoughts and behaviours between 2019 and 2021. We further investigate the relationship between suicidality and feelings of sadness and hopelessness and identify particularly vulnerable groups in Luxembourg’s young population.

Jump to content

What does suicidality mean?

In this policy brief, suicidality encompasses a range of behavioural patterns including contemplating and planning a suicide as well as attempting suicide at least once during the past 12 months. The term sadness describes the feeling of sadness or hopelessness over at least two consecutive weeks during the last 12 months.

Suicidality before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

According to the Direction de la santé, there was a total of 10 suicides in 2019 in the age group of 15 to 29-year-olds. No data is available for 2021 yet and conclusions about the change in suicide rates cannot be drawn at this point (Weber et al. 2021).

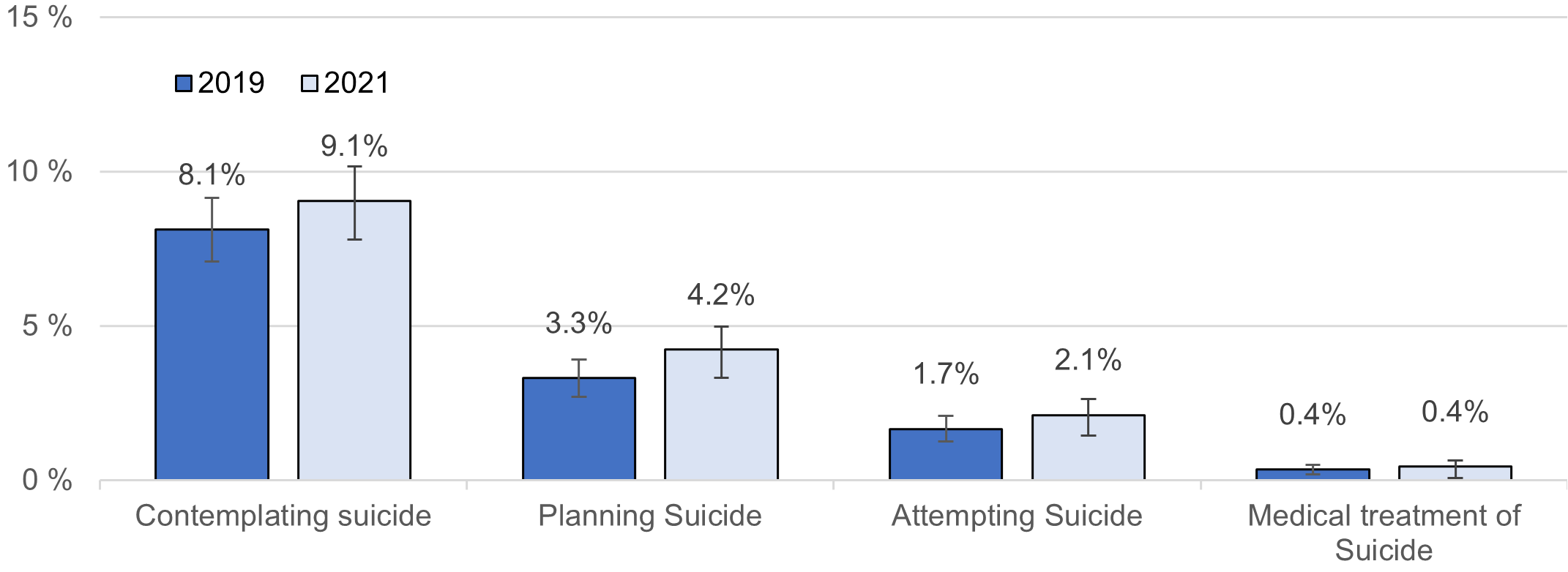

According to our results, the proportion of young people in Luxembourg who – in the previous 12 months – considered committing suicide ranges from 8 % (2019) to 9 % (2021); 3 % (2019) to 4 % (2021) planned to commit suicide; 2 % attempted suicide and about 0.4 % were treated by a doctor or nurse because of their suicide attempt (see Figure 1).

Overall, the current YSL (2019) and YAC (2021) data show no statistically significant shifts in suicidal thoughts and behaviour between the pre-pandemic situation in 2019 and the situation during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in the summer of 2021.

Changes can be seen, however, in the relationship between age and socioeconomic status (SES) with the consideration of suicide. Compared to 2019, differences by SES have increased across all age groups in 2021. Respondents with low SES are more likely to have considered suicide than respondents with medium or high SES across all age groups.

Relation between sadness and suicidality

We could find a strong relationship between sadness and the consideration of suicide as well as sadness and the planning of suicide. This suggests that sadness felt over a long period could be a warning sign of suicidality.

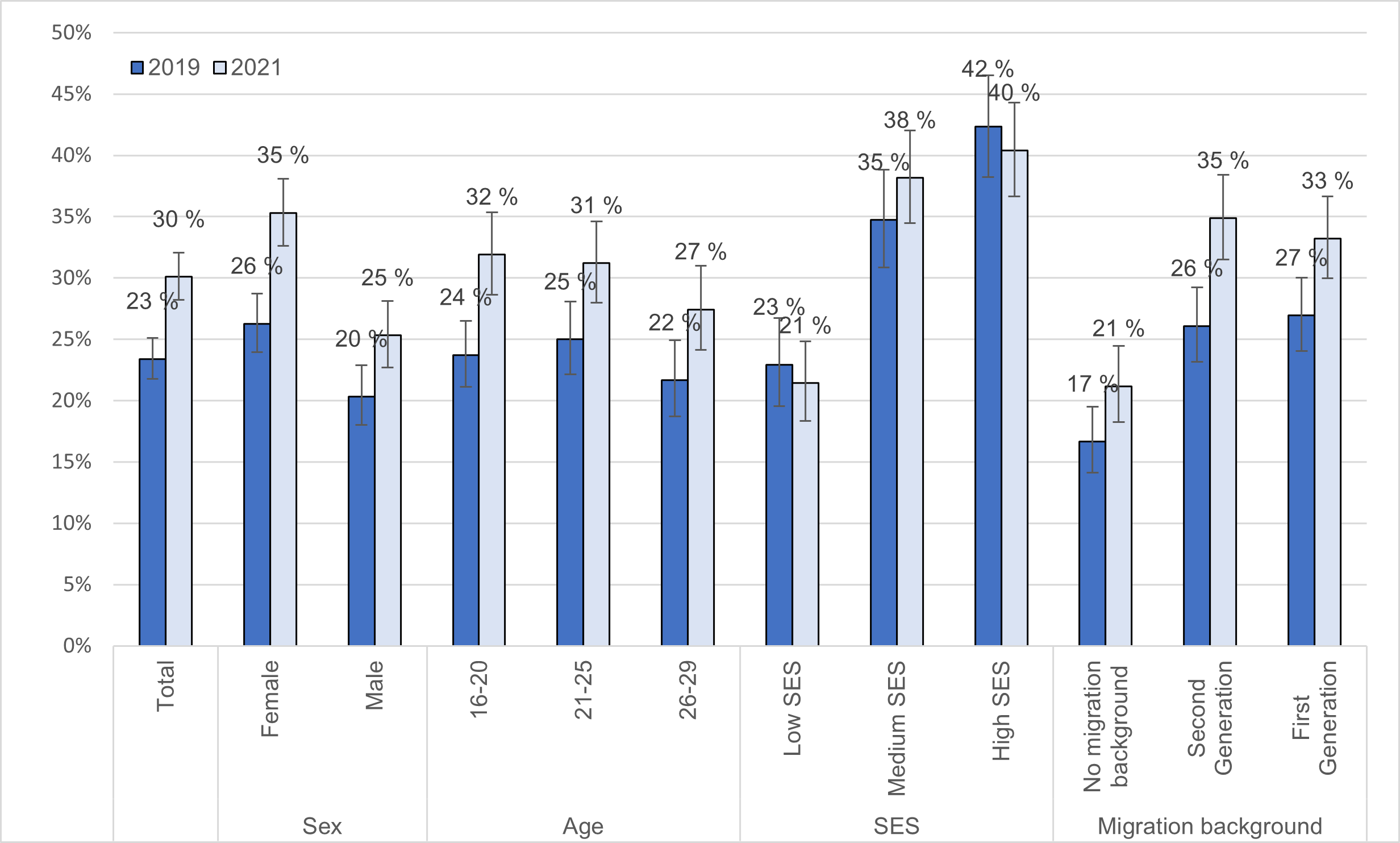

We find significant increases between 2019 and 2021 in the number of respondents who felt sad and hopeless across all subgroups of gender, age, SES, and migration background.

Furthermore, we find a significantly higher probability for young girls and women to experience prolonged sadness compared to their male peers. This effect is more pronounced in 2021 than it was in 2019. However, some studies have found a contradictory relationship between gender and suicidality: while considering and attempting suicide is more common among female adolescents, male adolescents show higher rates of completed suicides. Some researchers argue that this paradox is related to the higher prevalence of externalizing disorders (e.g. risk-taking; drug and alcohol consumption) among male adolescents and young adults compared to their female peers. This should be considered when establishing prevention measures.

Shifts by age and SES are also evident: While in 2019 the differences in feeling sadness by age and SES are still marginal, data from 2021 show clear differences between respondents with low, medium, and high SES. This indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has further increased social inequality and made previously vulnerable groups even more vulnerable.

As perceived persistent sadness correlates with contemplating and planning suicide, this relationship needs to be taken seriously and monitored further. Additionally, international research results show that crises are reflected in suicidal behaviour only after a delay. To be able to react to a deterioration of the situation in time and with suitable instruments, further observation, and research on the suicidal behaviour of young people is of utmost importance.

Policy Recommendations: Strengthen psycho-social professionals and expand services

- The availability and access to mental health professionals and services need to be expanded and low threshold. Here, different prevalence and vulnerabilities in groups (e.g., young females; low SES) should be considered when addressing and designing measures.

- Local suicide prevention activities should be sustainable over time to ensure continuity and consistency of services.